Over the past decade, immigration and globalization have significantly altered Europe’s cultural and ethnic landscape, foregrounding questions of national belonging. In

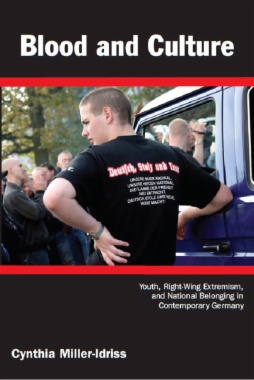

Blood and Culture, Cynthia Miller-Idriss provides a rich ethnographic analysis of how patterns of national identity are constructed and transformed across generations. Drawing on research she conducted at German vocational schools between 1999 and 2004, Miller-Idriss examines how the working-class students and their middle-class, college-educated teachers wrestle with their different views about citizenship and national pride. The cultural and demographic trends in Germany are broadly indicative of those underway throughout Europe, yet the country’s role in the Second World War and the Holocaust makes national identity, and particularly national pride, a difficult issue for Germans. Because the vocational-school teachers are mostly members of a generation that came of age in the 1960s and 1970s and hold their parents’ generation responsible for National Socialism, many see national pride as symptomatic of fascist thinking. Their students, on the other hand, want to take pride in being German.

Miller-Idriss describes a new understanding of national belonging emerging among young Germans—one in which cultural assimilation takes precedence over blood or ethnic heritage. Moreover, she argues that teachers’ well-intentioned, state-sanctioned efforts to counter nationalist pride often create a backlash, making radical right-wing groups more appealing to their students. Miller-Idriss argues that the state’s efforts to shape national identity are always tempered and potentially transformed as each generation reacts to the official conception of what the nation “ought” to be.